Central Banks need to reduce inflation, even if that means pushing their economy into recession

- 9 Mar 2023

- Analytics Consulting

- LinkedIn Profile

Introduction

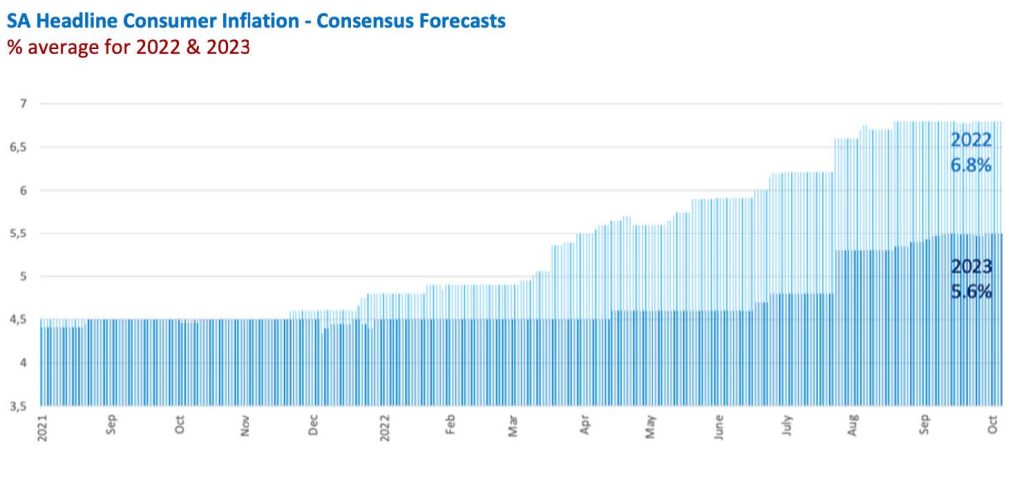

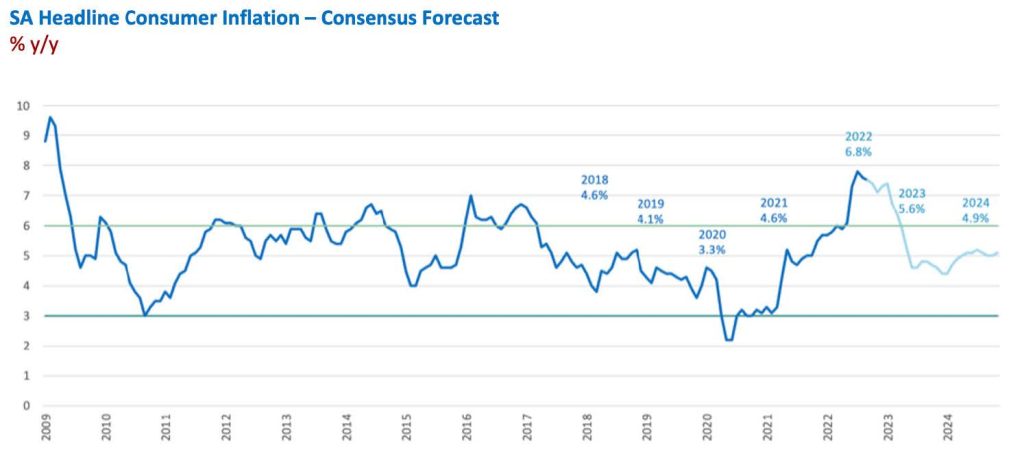

In a matter of 12 months, the forecast for South Africa’s average inflation rate during 2022 has moved from the mid-point of the target range at 4.5% to well above the target at 6.9%. However, inflation is expected to revert to the mid-point of the target range by the end of 2023. With this in mind, it might be perplexing that, around the world, inflation is expected to subside during 2023, while at the same time economic growth is forecast to weaken further, yet most Central Banks are expected to either continue to raise interest rates or at least maintain high interest rates well into 2023.

From a Central Bank’s perspective, monetary policy needs to remain restrictive until it is abundantly clear that inflation is under control, even if it means pushing their economy into recession.

Furthermore, the outlook for inflation remains highly uncertain, which continues to have a significant impact on financial markets. Consequently, strong and sustained policy action is needed to bring inflation and inflation expectations down. Delaying the tightening of monetary policy usually means that when interest rates are finally increased, they have to rise far more than what would have been the case had the authorities acted more promptly.

Despite headline inflation trending lower due to base effects, real inflationary risks remain. These include the possibility of prolonged supply disruptions, rising geopolitical tension, higher commodity prices (including the oil price), or simply the de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Inflation expectations, in particular, play a significant role in determining inflation outcomes. It is therefore understandable that policymakers need to remain vigilant and ready to act should further inflationary pressure start to emerge.

Why is high inflation problematic?

Sustained high inflation erodes or discourages savings, inhibits growth by depleting spending power, exacerbates the income wealth divide and social unrest, makes economic planning and budgeting difficult, discourages investment into productive assets and stimulates capital outflows. Given these factors, the primary goal of monetary policy is to keep inflation low and retain price stability, creating the necessary conditions for fixed investment and sustainable higher economic growth.

In trying to control inflation, many central banks make use of an inflation target to guide monetary policy and the setting of interest rates. Keeping inflation within the target improves the predictability of investment and savings returns and provides clear price signals to economic participants. If most participants in the economy know that inflation will remain within target, they will act accordingly.

The inflation targeting framework has clear metrics and is transparent. In the past, some policy makers argued that higher inflation would boost growth, only to find that it resulted in stagnation. Thereafter monetary authorities started to target money supply growth or the exchange rate as a means to subdue a build-up inflationary pressure. Unfortunately, this also proved to be largely ineffective. While controlling the amount of money in the economy had some success in controlling inflation, it failed to anchor inflation expectations since the demand for money is relatively unstable. Instead, inflation targeting provides a predictable framework that allows the Central Bank to forcefully respond to the emergence of inflationary pressure.

Understandably, the extent of any monetary policy response needs to be carefully considered and calibrated to the prevailing inflation dynamics, namely, the extent to which price shocks are merely pushing up headline inflation or feeding into a broad-based increase in prices. If headline inflation rises above core inflation, but then quickly slows back to its long-term trend, it cannot be argued that there are second-round effects present in the economy. However, if in a few months, core inflation rises to catch up with the trajectory of headline inflation, then second round effects are present.

Each country’s unique underlying dynamics pose different risks. In the case of South Africa, changes in food and energy prices have a significant effect on households’ cost of living due to their disproportionally large weight in the consumption basket – and therefore also have a large impact on inflation expectations. In that regard, it is well documented that rising inflation expectations drive demands for higher wages as workers try to restore real consumption levels. Consequently, a supply-side shock can easily result in a wage price spiral.

In this context, the structure of labour markets and the wage-setting process are key considerations. In the US, for example, labour markets are tight and a wage price spiral normally emanates from the a labour demand/supply imbalance. In contrast, in South Arica there is an abundance unskilled labour but large and effective trade unions that are able to negotiate for significantly higher wages, despite an extraordinary high level of unemployment.

Lastly, in many countries, including South Africa, institutional and regulatory barriers (including administered prices) can hinder the impact of higher interest rates in controlling prices. In particular, the cost of education, electricity, communication, water and transport. Fortunately, anchoring inflation expectations partly assists in addressing this dynamic.

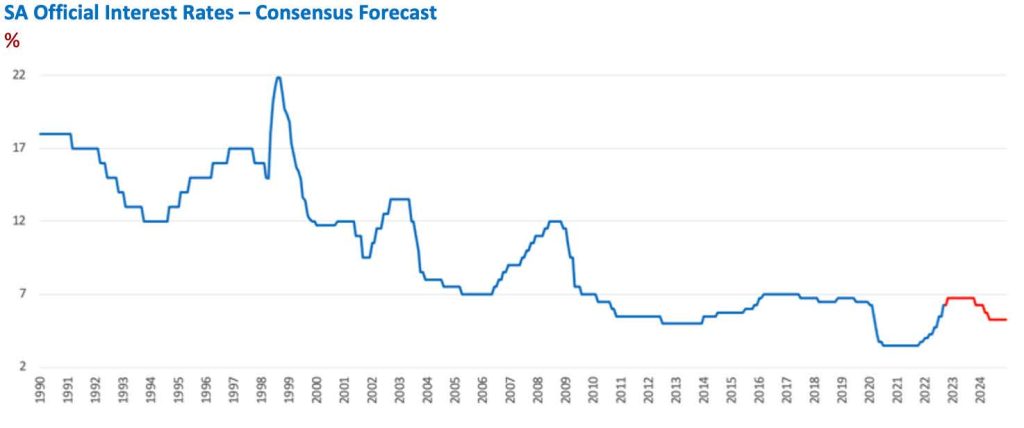

Inflationary pressures are expected to ease in 2023

Falling commodity prices, easing supply constraints and the recent monetary tightening should contribute to a declining inflation trajectory in 2023. Under current circumstances, we expect that the Reserve Bank will hike rates by another 25bps in March and then allow interest rates to move sideways during 2023 as they assess the impact of higher interest rates on inflation and economic growth. This opens-up the possibility that the Reserve Bank could consider cutting interest rates by the end of 2023. Understandably, however, if headline inflation does not slow convincingly, or core inflation does not follow the trajectory of headline inflation, then the Reserve Bank will be forced to keep interest rates elevated for longer, and only look to reduce interest rates in 2024.

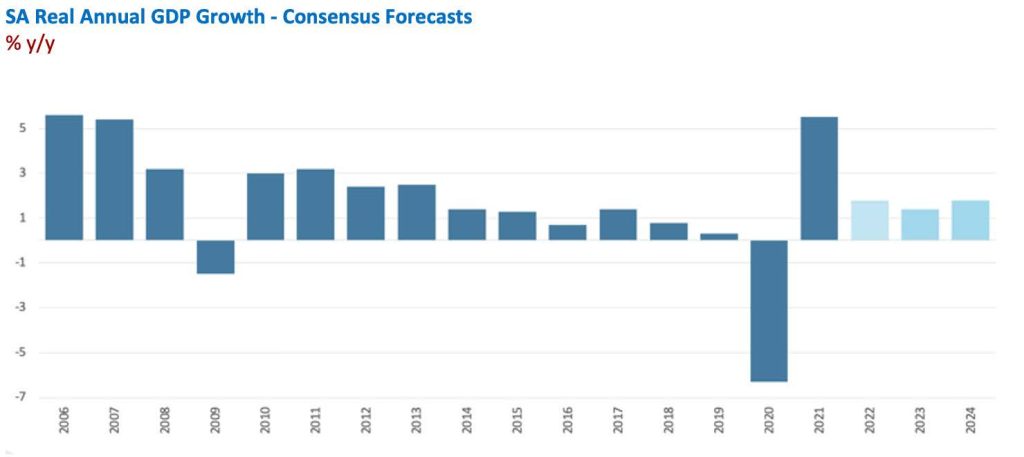

Lastly, the policy of inflation targeting has often been described as ignoring growth. However, by ensuring that monetary policy is unwavering in its efforts to control any sustained upsurge in prices, inflation tends to remain range-bound for extended periods, allowing central banks to restimulate economies and lower rates during periods of economic weakness. All of this suggests that South Africa can anticipate an upswing in economic activity during 2024, supported by low inflation and a systematic reduction in interest rates.

Written by: Alison Barker, Analytics Consulting